This section provides relevant contextual background to the issue of civilian firearms possession in Ukraine. It begins by considering indicators of insecurity in Ukraine, before highlighting the perceived role of weapons in addressing such insecurity and the specific perspectives and needs of the veteran and combatant population in Ukraine.

(In)security away from the front line

Security is precarious in the regions of Ukraine affected by the Russian Federation’s ongoing military attacks. In the context of a front line spanning 1,200 km, large parts of the Ukrainian population are exposed to significant physical danger, prompting a mass exodus from the front-line areas to safer regions of the country or abroad.[1] Even far from the front line, aerial attacks undermine many residents’ sense of security. According to our December 2023 survey, about one in five Ukrainians (21 per cent of survey respondents) indicated that shelling, aerial bombing, or drone attacks happened quite frequently or very frequently in their area.

Following the outbreak of the conflict in the eastern part of the country from 2014, Ukraine experienced a substantial increase in criminal violence until 2017,[2] raising concerns that a similar spike in violence could occur after the 2022 invasion. The likelihood of history repeating itself remains a significant concern. Indeed, after the 2022 Russian invasion leaders of criminal groups reportedly relocated and moved assets abroad, but more recent reports suggest a resurgence in organized criminal activity in Ukraine. In addition to drug and weapons trafficking, these criminal organizations also appear to be facilitating draft dodging (Global Initiative, 2023).

Our latest research reveals that, as of December 2023, survey-based crime victimization levels are only slightly elevated when compared to previous periods. The annual victimization rate, which stood at 3.4 per cent during peacetime in 2011, increased to nearly 7 per cent in 2019 and reached approximately 8 per cent in 2023 (see Table 1).

The proportion of victims who reported that a firearm was used in at least one of the crimes they experienced over the previous 12 months has substantially increased, however (see Table 2). The proportion of those reporting firearms use (which can include the mere presence of a firearm during the commission of a crime without the weapon being fired) almost doubled from less than 6 per cent of victims at the outset of the full-scale war to nearly 11 per cent in December 2023.[3]

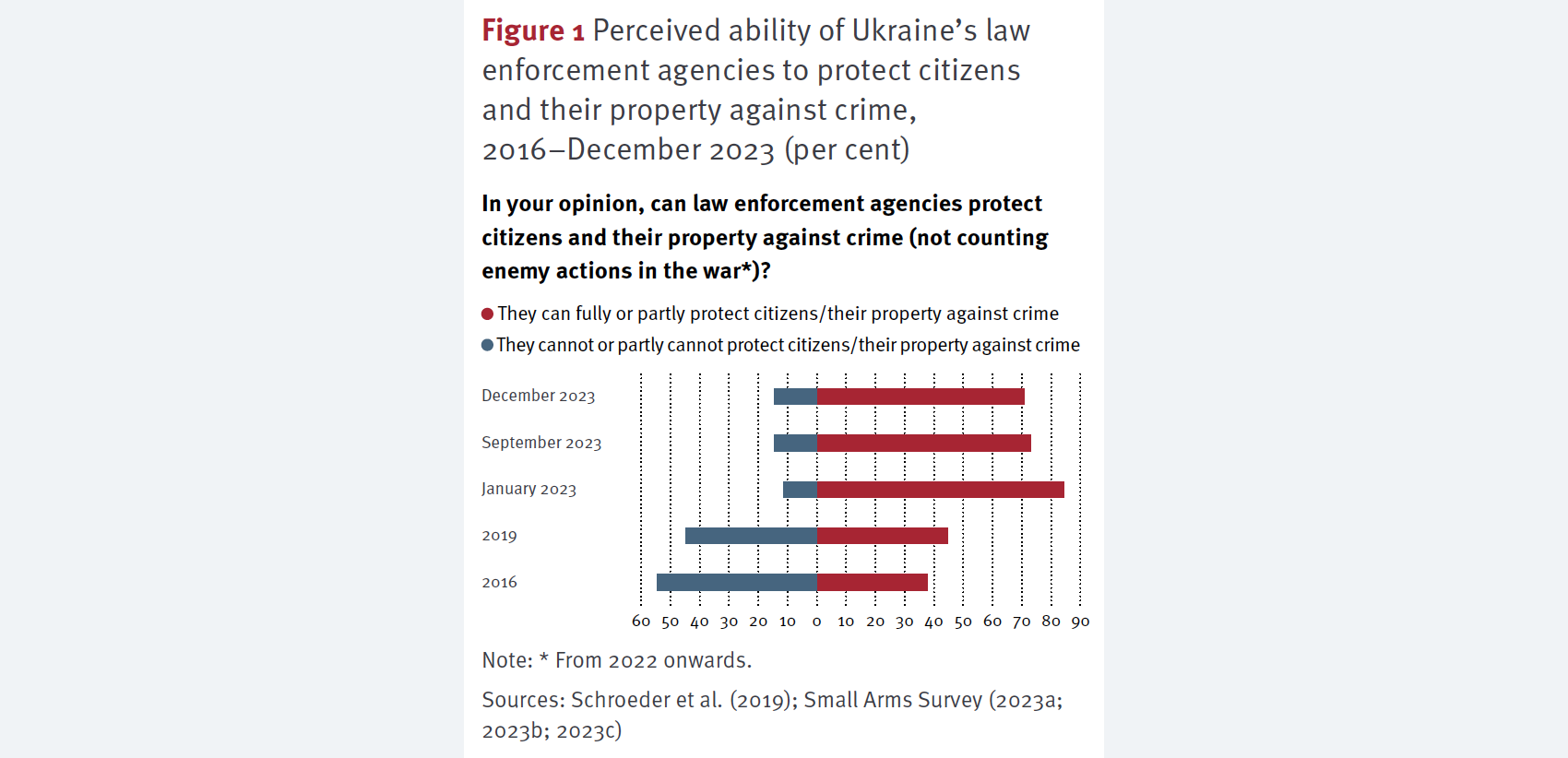

Survey responses also suggest that Ukrainian adults were less concerned about crime in December 2023 than they were prior to the full-scale Russian invasion. This sentiment is reinforced by the general population’s continued high regard for policing: the vast majority of respondents believe that law enforcement agencies are able to protect citizens against conventional, non-war-related crimes (see Figure 1).

Private means of protection

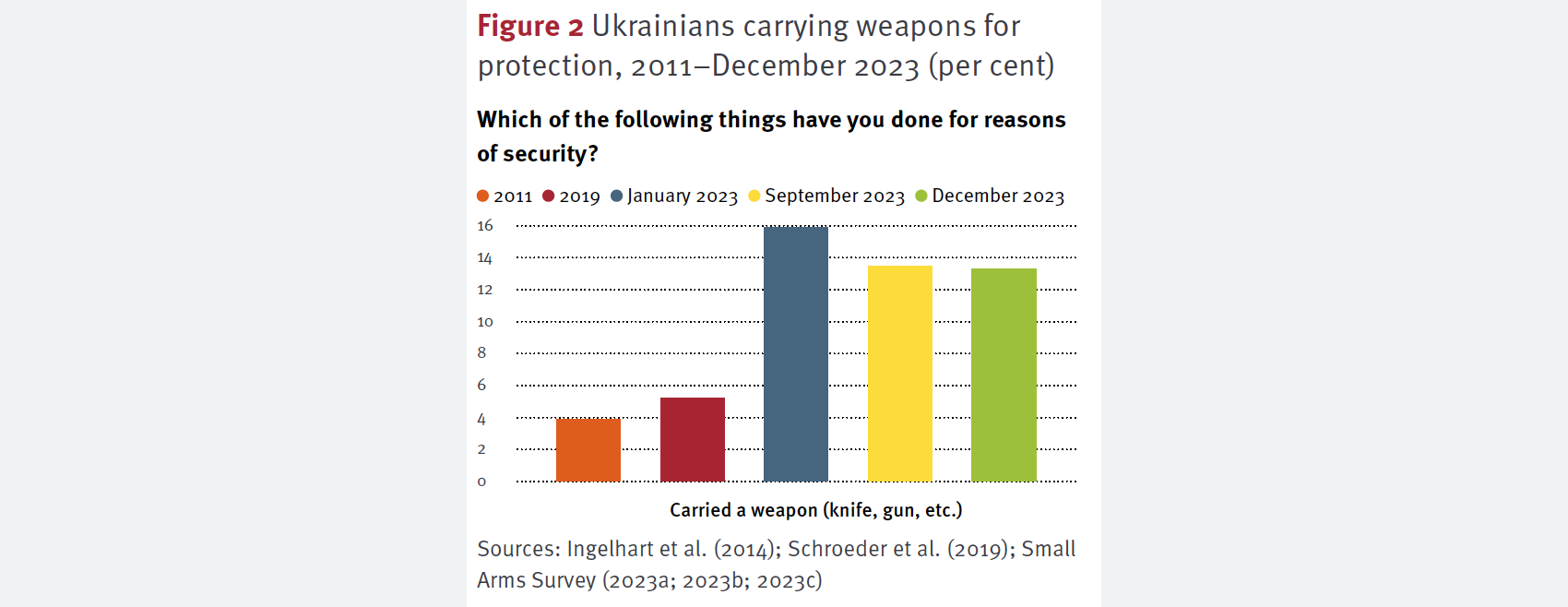

Ukrainians have changed the ways in which they are seeking to protect themselves from threats to their security. The proportion of respondents arming themselves for self-defence—with various types of weapons, including traumatic weapons, firearms, knives, and pepper and gas sprays—tripled between 2011 (3.9 per cent) and December 2023 (13.3 per cent) (see Figure 2). Based on the available data, reliance on these weapons for protection surged after the Russian invasion of 2022 and remained high and relatively steady until December 2023. Despite reports of growing popular support for liberalizing civilian firearm ownership in Ukraine,[4] our latest survey did not find a significant increase since 2022 in the number of people carrying a firearm to protect themselves. In fact, the proportion of respondents that reported carrying a firearm for protection remained stable and low—at about 2 per cent—between January 2023 and December 2023.

As of December 2023, 18.3 per cent of the surveyed adult males indicated that they at least sometimes carried some form of weapon for security purposes, and nearly 5 per cent reported carrying firearms for self-defence. While, overall, firearms represent a small proportion of the weapons being carried for protection, they are particularly popular among certain population subgroups. Among men in households with at least one veteran from the previous Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) or current war, 33 per cent carry a weapon for protection and 14 per cent carry a firearm. Moreover, more than 4 per cent of Ukrainian men aged 18 or more indicated that they acquired a firearm during the previous 12 months ‘for reasons of security’—compared with about 2 per cent of all respondents.

In the December 2023 survey not a single responding woman stated that she carried a firearm to protect herself (compared to 0.5 per cent in the previous survey). Many women, however, especially young women, carry some other form of weapon for protection (9 per cent on average, with this figure rising to 22 per cent among women below the age of 30).

Specific perceptions and needs of veterans

Similar to what occurred after the 2014–15 phase of the war, the current phase is creating a growing population of young and not-so-young[5] men with combat experience (Snodgrass, 2023)—many of whom may lack stable employment or a home to return to at the end of their period of service. Some of these men are expected to struggle to reintegrate into civilian life,[6] and there is a risk that many may bring their military firearms with them when they return to their communities. Data from the December 2023 survey indicates that 38 per cent of all respondents believe it is likely that Ukrainian soldiers will retain some of their firearms instead of handing them in to the authorities.

Many of the demobilized personnel will probably also be dealing with recent trauma, including psychological and physical, which could further complicate their reintegration into civilian life and potentially making them more susceptible to engaging in criminal activity or other forms of violence, including political and domestic violence (Guest et al., 2022). Previous research indicates that trauma afflicting former combatants correlates with mental problems and substance abuse, which in turn increase the likelihood and severity of violent behaviour, including intimate partner violence.[7]

[1] As of April 2024, of the pre-2022 population of about 44 million, the International Organization for Migration estimates there are about 3.5 million internally displaced persons and 4.7 million returnees (who previously were refugees or internally displaced individuals) in Ukraine (IOM, 2024). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees tracks about 6.8 million Ukrainian refugees outside of the country (UNHCR, 2024). Overall, internal or external displacement affected about one-third of the population.

[2] See Hideg (2023).

[3] Considering that many of the crimes people encounter as victims do not involve any contact (burglary, vandalism, theft, etc.), this seems to be a fairly high proportion. Unfortunately, the Small Arms Survey does not have directly comparable data from other countries.

[4] The 2019 survey found that only 23 per cent of respondents supported the legalization of firearms for citizens (Schroeder et al., 2019), whereas surveys now find majority support for liberalization. Additionally, legislative actions are anticipated to address the issue in the near future (ALI, 2023).

[5] In the sample of the December 2023 wave of our survey series, 77 per cent of those who have been fighting in either the previous or the current stage of the war are between 30 and 59 years old.

[6] See research about the problems affecting the reintegration of Joint Forces Operation/Anti-Terrorist Operation veterans (Guest et al., 2022). This is not specific to Ukraine, and reintegration difficulties have also been observed in other post-conflict settings, including elevated levels of violence among former conflict participants (Bradley, 2018).

[7] For example, OSCE (2020, pp. 59–62).

| < PREVIOUS | NEXT > |