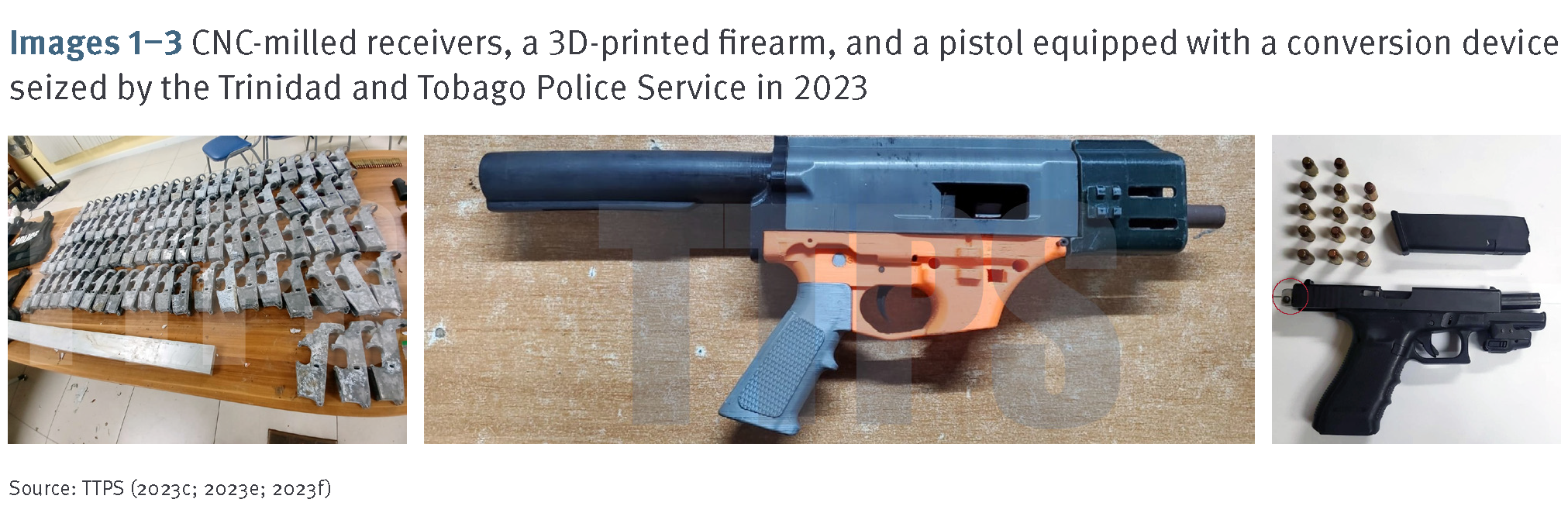

New data reviewed in this Situation Update shows that while PMFs probably still account for a minority of firearm seizures in the Caribbean, the rapid evolution of techniques for producing these weapons has led to the circulation of a broad range of PMFs in the region. Since the Survey and CARICOM IMPACS published their regional report on illicit firearms in the Caribbean in April 2023, three trends have been particularly noteworthy: the significant seizures of privately made pistols, rifles, and their parts—including partially finished frames and lower receivers produced with CNC milling machines; the dismantlement of the first 3D-printed firearm workshops and equipment in the region; and the continued proliferation of conversion devices (see Images 1–3). Data limitations—including a general lack of awareness and training among law enforcement, customs officials, and the media—suggest the scale of these trends may be even more significant than publicly reported.

As argued in the Caribbean Firearms Study, the decentralized community of amateur gunsmiths involved in advancing techniques for the production of PMFs is continuously refining its methods to quickly adapt to and circumvent new firearm-related restrictions. This situation calls for improving regional capacities for ‘accurately and consistently identifying ghost guns, 3D-printed firearms, and other PMFs’, including through the provision of up-to-date weapons identification training to relevant agencies (Fabre et al., 2023, p. 90). It is also critical to ensure that information on the latest PMF-related trends is shared regularly with authorities from throughout the Caribbean so that appropriate prevention and mitigation measures can be put in place in a timely manner. The development of region-wide firearm-related crime intelligence capabilities—for instance, through the recently created CARICOM Crime Gun Intelligence Unit[13]—can help detect and track emerging types of illicit firearms.

Tackling the trends noted above is not only a matter of law enforcement; PMFs also risk affecting Caribbean societies in broader ways. The proliferation of components used for assembling privately made firearms, and of conversion devices that enable handguns and rifles to shoot in automatic mode, may provide criminals with more diverse ways of acquiring reliable semi- and fully automatic weapons, which would put both law enforcement officers and wider communities at greater risk. Investigative media reports suggest that pistols converted to automatic fire are already in high demand among local gangs in countries such as Trinidad and Tobago (Trinidad and Tobago Guardian, 2023). The emergence of 3D-printed firearms adds a layer of complexity to these challenges, as 3D printers are becoming cheaper, have many legitimate purposes, and are generally not restricted to any particular age group.

The further proliferation of PMFs may therefore increase the regional availability of semi-automatic and fully automatic weapons, which can also have significant public health implications. Fully automatic weapons are more difficult to handle and aim, and consequently their use may result in more deaths and injuries among the intended targets and bystanders.[14] In St Lucia, for instance, during a shooting incident in Vieux Fort on Independence Day (22 February 2024), six people sustained gunshot wounds, three of whom died from their injuries (The Voice SLU, 2024a). According to the authorities, a firearm equipped with a conversion device was used in this attack.[15]

Focus group discussions revealed little awareness among participating public health practitioners about the threat of PMFs. Nevertheless, one participant noted a general increase in the victimization of young children as bystanders in their country.[16] Doctors from the Bahamas and Jamaica separately observed a trend towards the increasing use of firearms with an intent to kill, resulting in a higher number of ‘deaths upon arrival’ with multiple injuries at hospitals.[17] Attributing these trends to the proliferation of PMFs specifically would require access to additional data on the types of weapons and ammunition used in shootings from forensic pathologists and experts. This information is not, however, readily accessible or systematically collected. Seizure data, death certificates, and other public health records currently do not always capture detailed information about the types of firearms used in shootings, including whether they might have been PMFs or converted.[18] It will therefore be crucial to improve the level of detail of firearm-related data captured by seizure databases as well as mortality and injury surveillance systems moving forward to better monitor and assess the public health impact of emerging firearm-related threats.

Despite data limitations, evolving injury patterns are illustrative of how the use of semi- and fully automatic weapons in crime—which the proliferation of PMFs risks exacerbating—might impact victims and communities. While the public health sector in the Caribbean generally possesses the required facilities and surgeons to provide appropriate care to patients with firearm injuries,[19] an increase in the number of individuals presenting to the emergency department with serious wounds has the potential to overstretch the healthcare system. This is especially worrying for the smaller islands where few doctors are available in emergency rooms at a given time. Indeed, operating on a patient with multiple firearm injuries can occupy a surgeon for hours, causing long delays for other patients requiring other types of urgent care.[20] The threat of PMFs and conversion devices in the Caribbean should therefore not be taken lightly, and Caribbean governments need to be well prepared to prevent and mitigate its manifestations.

[13] For more information, see CARICOM (2024).

[14] For a discussion on the impacts of shooting incidents involving conversion devices in the United States, see City of Chicago (2024, pp. 4–5, 22–25).

[15] Confidential interview with a law enforcement official, St Lucia, 23 April 2024.

[16] The participating practitioners noted that it is generally not possible to ascertain definitively whether automatic weapons or PMFs were used based only on a review of the patients’ injuries. Online focus group discussions facilitated by the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) and the Small Arms Survey with medical practitioners from Aruba, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Grenada, Montserrat, and Trinidad and Tobago, 27 March and 8–9 April 2024.

[17] Online focus group discussion with doctors from the Bahamas and Jamaica, 30 April 2024.

[18] Online interview with Jamaican law enforcement officials, 24 May 2024.

[19] Online focus group discussions facilitated by CARPHA with medical practitioners from Aruba, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Grenada, Montserrat, and Trinidad and Tobago, online, 27 March and 8–9 April 2024.

[20] Interview with a public health expert, St Lucia, 25 April 2024.

| < PREVIOUS | BACK TO MAIN PAGE > |