This section reviews developments regarding the proliferation of PMFs in the Caribbean since April 2023. In this Situation Update, the Survey uses the US government’s definition of PMFs, which refers to ‘a firearm, including a frame or receiver, assembled by a person other than a licensed manufacturer, and not containing a serial number or other identifying marking placed by a licensed manufacturer at the time the firearm was produced’ (Office of the US Federal Register, 2022, p. 24664). As most types of PMFs do not include serial numbers and are therefore difficult to trace—at least through conventional methods—they are also often referred to as ‘ghost guns’.

Due to detection and reporting issues, it remains difficult to assess the true magnitude of the PMF threat in the region. Indeed, PMFs are rarely identified as such in open sources, and so careful examination of published imagery is often necessary to detect them. This section is based on a review of articles by news outlets and press releases by law enforcement agencies, supplemented by key informant and expert reviews. It begins by providing an overview of seizures of different variants of PMFs in the region from April 2023 to April 2024, before focusing more specifically on 3D-printed firearms and conversion devices.

Overview of PMF seizures since April 2023

PMFs illicitly assembled from partially finished and industrially produced components[1] are circulating in the Caribbean, as highlighted in the 2023 Caribbean Firearms Study, published by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Implementation Agency for Crime and Security (IMPACS) and the Small Arms Survey (Fabre et al., 2023, pp. 91, 95). The partially finished components—notably frames for pistols and receivers for rifles—are combined with other factory-built parts to produce a functioning firearm. In order to facilitate their assembly, these components are often packaged and sold as kits that also include the necessary production tools, such as drill bits and jigs. Tutorial videos are also available online (p. 91). While these PMFs can vary in quality and functionality, interviews conducted during the course of the Caribbean Firearms Study indicate that these kits allow for the production of durable and properly functioning firearms (p. 92).

Due to the availability of easy-to-follow instructions and materials with which ghost guns can be assembled, such as partially finished frames and receivers, this category of PMFs contributed to a substantial increase in PMF seizures in the United States. According to the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, recoveries of PMFs by law enforcement in the United States increased by 1,083 per cent between 2017 and 2021 (White House, 2024). In 2022, the US government sought to address the issue by expanding the definition of firearms and introducing new marking requirements for firearms components. At the time of writing, however, the legislation was still under review by the US Supreme Court (Chung, 2024).

The region’s proximity and extensive commercial trade with the United States means that traffickers can easily conceal these parts and kits in common household items, sometimes in separate packages in order to evade detection (Fabre et al., 2023, pp. 79–87). Data on US seizures of arms shipments bound for the Caribbean suggests that interdictions of illegally exported ghost gun components have levelled off in recent years. Between September 2021 and mid-December 2023, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) seized 81 receivers and frames/kits that were bound for the Caribbean, compared to 165 receivers and kits between 2016 and 2021. The average number of seizures of these items per month therefore increased slightly from 2.4 between 2016 and 2021 to 2.9 between 2021 and 2023.[2] Available data on seized components does not always make it possible to determine whether they were partially finished or intended to be used to build PMFs. Several recent cases show, however, that PMFs and components for assembling PMFs are being exported to the Caribbean, including the following examples:

- In December 2023, a US national was convicted of trafficking PMFs to the Dominican Republic. He purchased kits at gun shows, assembled them into functioning firearms in his workshop in Rhode Island, and then shipped the weapons to the Caribbean country. Court documents indicated that the trafficker procured and shipped 100 weapons to the Dominican Republic in this manner from 2017 to January 2022 (Henry, 2024).

- That same year, a resident of the US Virgin Islands was sentenced to ten years for manufacturing PMFs from packages of firearm components shipped from Florida and North Carolina (St. Thomas Source, 2023).

- In Trinidad and Tobago, recent suspected PMF seizures have included at least three instances of firearms built from 80 per cent receivers, although it is unclear where these components originated from (TTPS, 2023a; 2023c; 2024d).

Moreover, Jamaican officials revealed that the vast majority of ghost guns seized in their country are assembled using partially finished ‘Polymer 80’ frames and kits. These privately made pistols are sometimes used together with conversion devices to make them capable of automatic fire. Most rifle frames used to assemble PMFs in Jamaica are also partially finished 80 per cent lower receivers.[3]

Lower receivers that appeared to have been CNC-milled from blocks of metal have also been seized in the Caribbean. For instance, the police in Trinidad and Tobago successively recovered an initial 91 and then an additional 14 CNC-milled lower receivers for AR-15-pattern rifles in October and November 2023, respectively (CNC3 Trinidad and Tobago, 2023; TTPS, 2023f). CNC-milled receivers were also documented in Haiti (UNSC, 2023, para. 102).

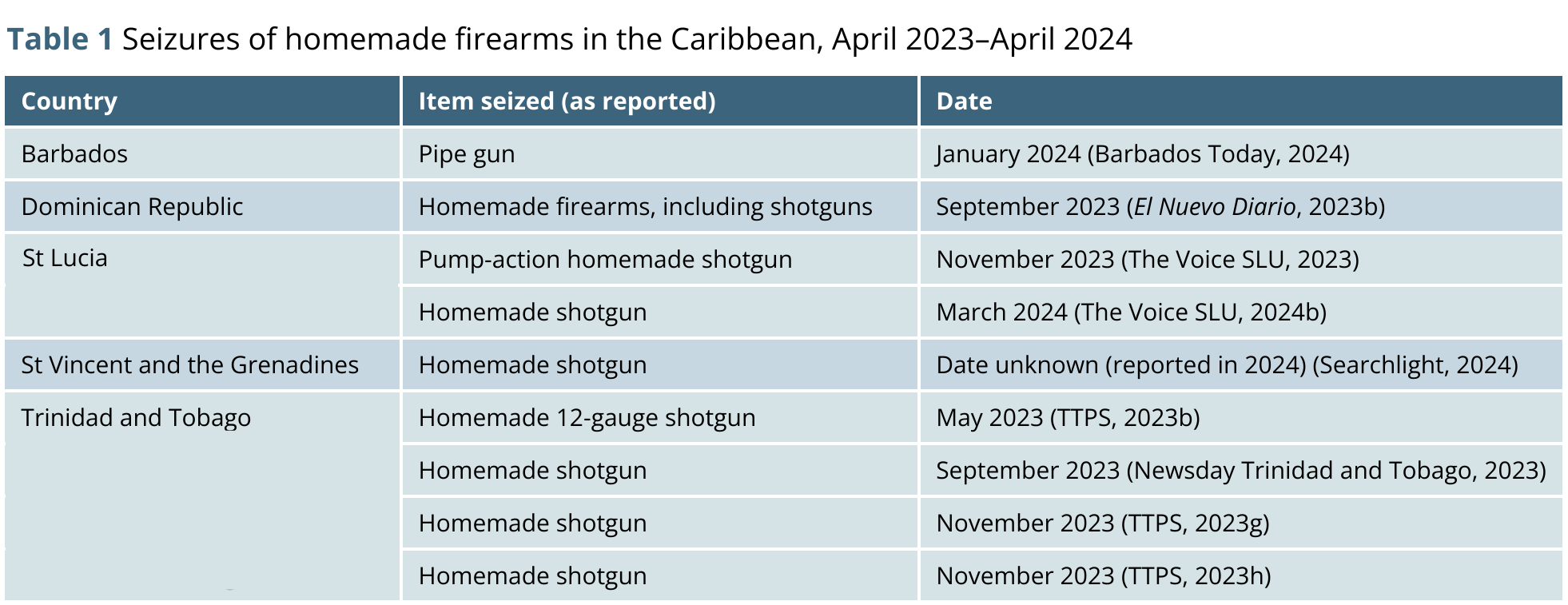

Other PMFs circulating in the region include rudimentary artisanal firearms. Between April 2023 and April 2024, homemade shotguns were seized in at least five countries and territories in the region (see Table 1). In the Dominican Republic, there have also been seizures of homemade pistols (El Nuevo Diario, 2023a). As the quality and reliability of some of these weapons can be poor (Barbados Today, 2024), it is unlikely that criminals will view them as a substitute for factory-produced weapons. Yet the threat posed by these weapons should not be underestimated, as they can be used in crime and therefore potentially contribute to the deterioration of the security environment.

Caribbean authorities have also seized modified flare guns, which are typically stolen from fishermen and then illegally altered to allow them to fire common ammunition such as 9 × 19 mm Luger (Fabre et al., 2023). Since April 2023, modified flare guns have been seized in Antigua and Barbuda (Williams, 2023) and Barbados (Clarke, 2023). Jamaican authorities have also seized small numbers of converted blank-firing alarm handguns (3–4 per year, usually in 9 mm PAK calibre and of Turkish manufacture).[4]

3D-printed firearms

3D-printed firearms are PMFs fabricated through the use of 3D-printing technologies. As 3D printers become cheaper and more advanced and user-friendly, 3D-printed firearms may become attractive to criminals and other individuals unwilling to take the risk of acquiring illicit firearms in the underground market (Fabre et al., 2023, pp. 97–98). For instance, a key informant from US Immigration and Customs Enforcement explained that criminal groups in Latin America and the Caribbean previously preferred to import factory-built frames and lower receivers for their quality. Today, however, they increasingly produce these components themselves using 3D printers—sometimes to sell the weapons to other criminals. These groups mainly need to import the barrel and trigger group to assemble a functioning firearm (US ICE, 2024).

3D-printed firearms potentially pose considerable challenges to law enforcement, including in terms of their detection, tracing, and investigation. Because such 3D-printed components are sometimes marked with the name of known firearms brands and combined with other industrially built components, law enforcement may not realize they are privately made, and describe them only as non-serialized firearms without indicating whether they are 3Dprinted (US ICE, 2024). The latest generation of 3D-printed firearms can be assembled exclusively from 3D-printed components, which further complicates efforts to trace their supply chain (Fabre et al., 2023, p. 98; Schaufelbühl et al., 2024). The chain of custody for 3D-printed firearms is also rather short, as it might only encompass a producer and end user, or even just one person if the producer is also the end user (Fabre et al., 2023, p. 98).

Concerns around the possible spread of 3D-printed firearms to the region were realized in August 2023, when a ‘ghost gun lab’ producing 3D-printed firearms for distribution to criminal groups was discovered in Trinidad and Tobago (Hamilton-Davis, 2023). The police recovered, among other items, a 3D printer and 3D-printing software, ammunition, and several 3D-printed firearms and projectiles at the workshop.[5] In separate incidents, authorities in Trinidad and Tobago have also seized what appears to be a 3Dprinted FGC9 (TTPS, 2023c), as well as a 3D-printed Glock lower receiver (TTPS, 2023d).

In 2023, authorities in St Lucia seized a 3D-printed semi-automatic firearm and a 3D printer.[6] Two 3D-printed firearms were also recovered in Antigua and Barbuda (Morgan, 2023). Similarly, there have also been a limited number of seizures of 3D-printed rifle receivers in Jamaica, but these appear to have been trafficked from abroad. To date, there have not been any reports of seizures of local workshops or equipment used to produce 3D-printed firearms in Jamaica.[7] While the number of documented cases of 3D-printed firearms remains limited, these incidents may represent only the tip of the iceberg as law enforcement techniques to detect such illicit manufacture are still emerging, and are not yet applied consistently.[8]

While some CARICOM member states have acknowledged that 3D-printed firearms are a threat to national security, only a few have adopted regulatory measures to curb their proliferation. St Vincent and the Grenadines, for example, is implementing new legislation that provides for stricter penalties for several offences, including the 3D-printing of firearms (Loop Caribbean News, 2024). Similarly, Jamaica passed the Firearms (Prohibition, Restriction and Regulation) Act in November 2022, which provides for an expansion of the definition of ‘firearms’ to include 3D-printed weapons, and prohibits the possession of digital blueprints of firearms and components with the intent to manufacture 3D firearms (Jamaica, 2022).

Conversion devices

Conversion devices include items referred to as ‘automatic switches’, ‘selector switches’, ‘Glock switches’, and ‘auto sears’. They are simple and easy-to-install accessories that convert semiautomatic handguns and rifles into fully automatic weapons (Fabre et al., 2023, p. 99). As such they make the weapon at hand more dangerous, as automatic fire may result in more injuries, including to bystanders.[9] Conversion devices also undermine firearms regulations that restrict civilian ownership of machine guns (p. 100). Conversion devices do not look like firearms or their main parts and are therefore difficult for untrained custom officials to detect. In fact, these devices have been sold online as household items such as coat hangers (p. 100). Reported cases therefore probably only capture a tiny percentage of illicit conversion devices circulating in the Caribbean.

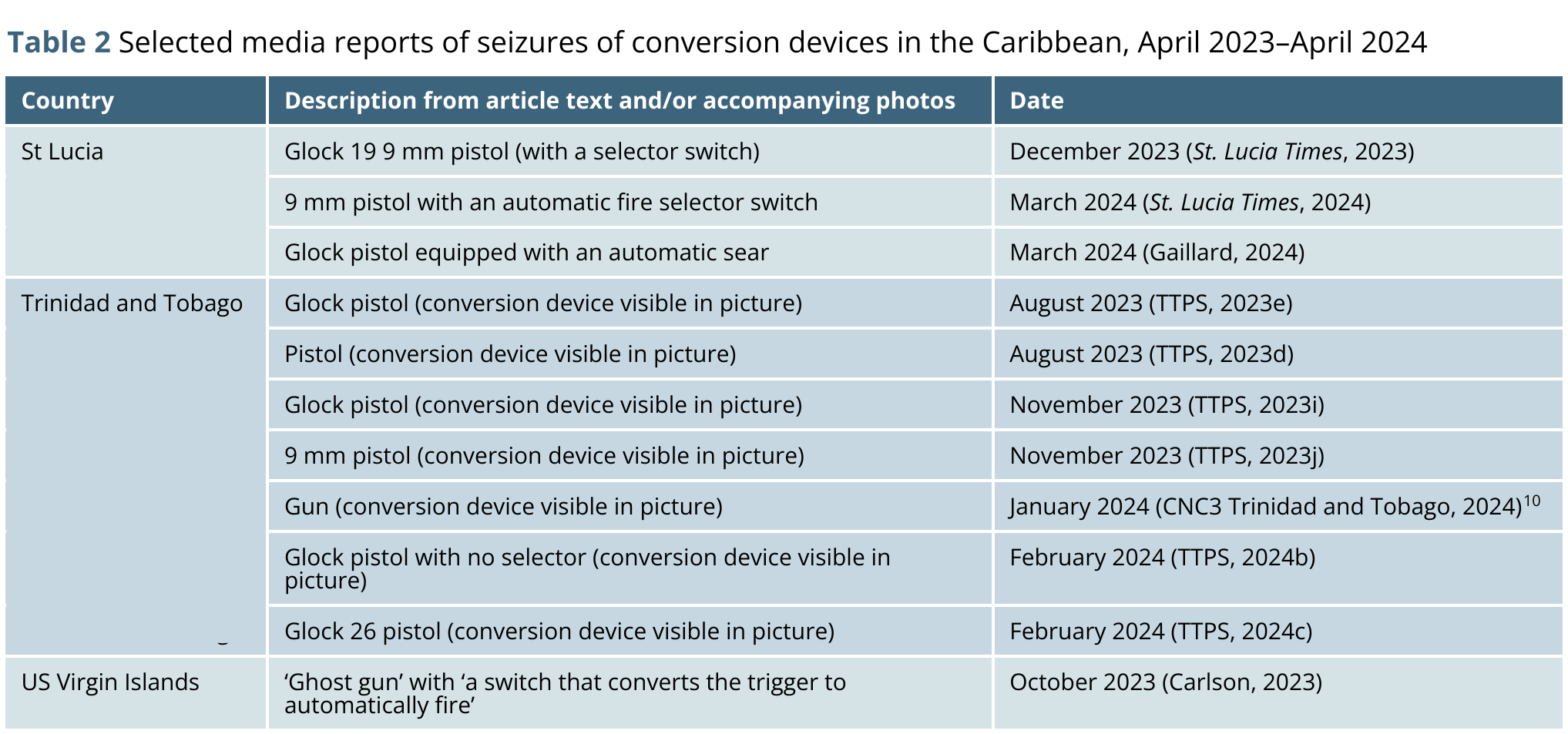

As reported in the Caribbean Firearms Study, the authorities of Trinidad and Tobago seized at least 57 conversion devices in 2020 and 2021 (Fabre et al., 2023, p. 100). Table 2 provides additional examples of conversion devices reportedly seized between April 2023 and April 2024. While most seizures occurred in Trinidad and Tobago, seizures of such devices have also reportedly occurred in St Lucia and the US Virgin Islands. These cases primarily concern the conversion of handguns, especially pistols manufactured by Glock, which is the most frequently reported firearm brand associated with conversion devices in the source documents reviewed for this Situation Update (see Table 2). Jamaican officials also report a steady increase in seizures of conversion devices, mostly installed on Glock-pattern handguns. In about three to four out of ten such seizures, the converted firearms were found to be tied to murder cases. In Jamaica, there have also been seizures of so-called ‘invisible switches’ that are not visible from the outside of the firearm; however, these particular devices remain quite rare and are not a growing trend.[11]

According to key informants, in a few instances conversion devices seized in Jamaica were acquired from websites based in the United States, but in most cases it was not possible to determine their origins.[12] Other sources explain that it is often easier to source these accessories from other countries. Some devices seized in the region are reportedly purchased online and shipped from China (US ICE, 2024).

[1] These items are variously referred to as ‘receiver blanks’, ‘unfinished receivers’, and ‘80 per cent receivers’.

[2] Data shared by US CBP in response to a Small Arms Survey Freedom of Information Act request, 15 December 2023.

[3] Online interview with Jamaican law enforcement officials, 24 May 2024.

[4] Online interview with Jamaican law enforcement officials, 24 May 2024.

[5] Correspondence with CARICOM IMPACS, November 2023; Hamilton-Davis (2023).

[6] Confidential interview with a law enforcement official, St Lucia, 23 April 2024.

[7] Online interview with Jamaican law enforcement officials, 24 May 2024.

[8] For an overview, see Schroeder et al. (2023, pp. 11–14).

[9] The City of Chicago documented a series of shooting incidents involving converted Glock pistols that caused casualties among bystanders. These concerns led the City of Chicago to file a complaint against Glock Inc. over the convertibility of its handguns through the use of such conversion devices. See City of Chicago (2024, pp. 4–5, 22–25).

[10] See also TTPS (2024a).

[11] Online interview with Jamaican law enforcement officials, 24 May 2024.

[12] Online interview with Jamaican law enforcement officials, 24 May 2024.

| < PREVIOUS | NEXT > |